A lesson in SSR safety that every DIYer needs to know before wiring a high-power load.

I was in the middle of a project I was really excited about—a little DIY temperature controller for my electric smoker. I’d mapped it all out. A simple controller, a temperature probe, and a Solid State Relay (SSR) to quietly switch the smoker’s heating element on and off. SSRs are great for this; they’re silent, fast, and have no moving parts to wear out. But as I was about to wire up the high-voltage side, I had a thought that stopped me cold: What if this thing fails? It’s a simple question, but the answer is incredibly important, and it’s the foundation of real SSR safety.

If you’re using an SSR to control anything that could be dangerous if it’s stuck on—like a heater, a motor, or anything with significant power—you need to hear this.

The Scary Truth About How SSRs Fail

Here’s the thing they don’t always tell you in the product description: When Solid State Relays fail, they most often fail closed. In plain English, they fail in the “on” position.

Think about that. If your SSR fails while controlling a heating element, that heater will be stuck on, getting hotter and hotter with no way to turn it off. The controller’s brain can send “off” signals all day long, but the physical switch inside the SSR is broken and permanently letting power flow through. This is how fires start. It’s not a theoretical risk; it’s a well-known failure mode for these components, often caused by overheating or a voltage spike.

This isn’t to say SSRs are bad. They’re amazing. But you can’t trust them with your safety. You have to plan for their inevitable failure.

My First Rule of SSR Safety: Assume It Will Fail On

Once you accept that the SSR will eventually fail and get stuck in the “on” position, the solution becomes obvious. You need a backup plan. You need a second, more traditional switch that can cut the power if the SSR goes rogue.

This is where a good old-fashioned mechanical relay or contactor comes in.

My safety strategy is simple: The SSR does all the heavy lifting—the rapid, precise switching to maintain temperature. But it only gets power when a master mechanical relay is also on.

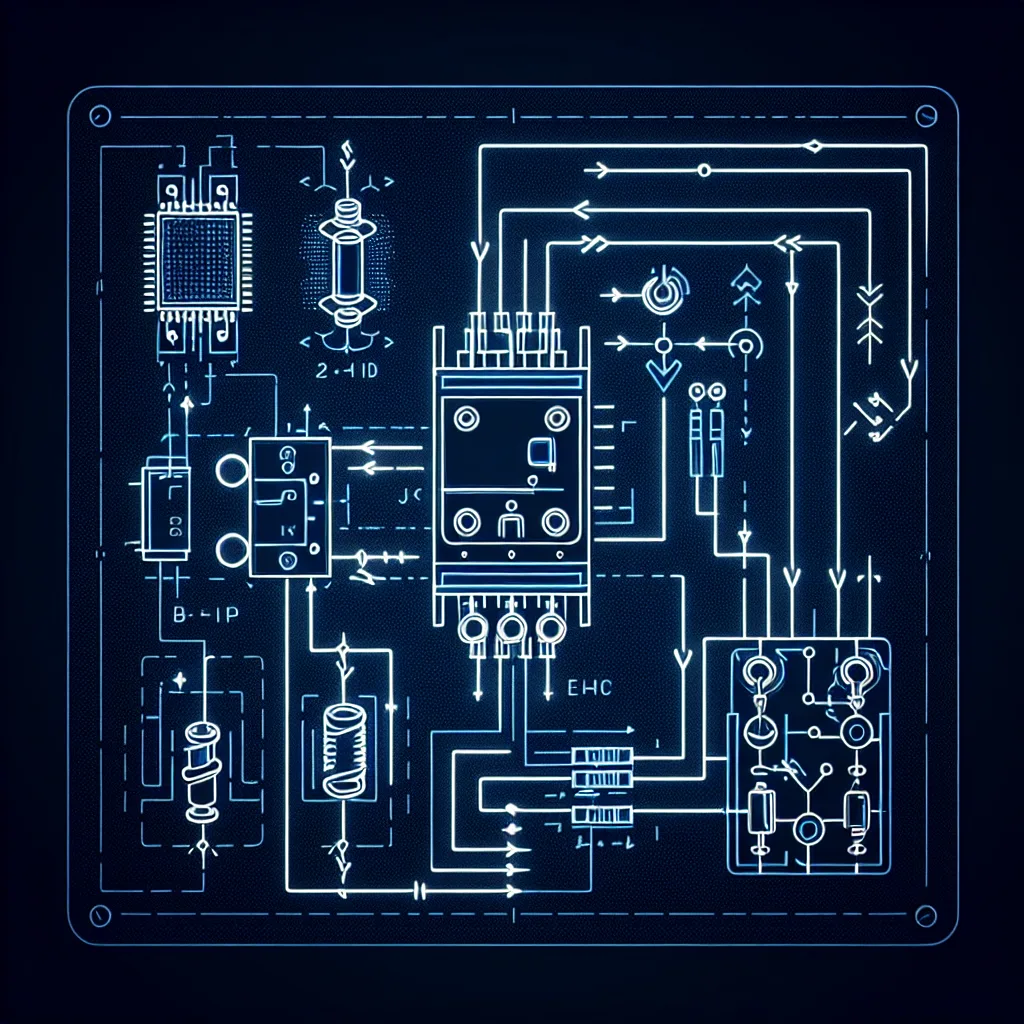

Here’s the setup:

* The Solid State Relay (SSR): This is the workhorse. It’s wired to the heating element and switches on and off every few seconds or minutes as needed.

* The Mechanical Relay (Contactor): This is the fail-safe. It’s wired in series with the SSR, meaning power has to flow through it first to even get to the SSR. This relay isn’t switching rapidly. It only turns on when I start a cooking session and turns off when I’m done.

If the SSR fails closed, the heating element is still connected to a rogue “on” switch. But since the mechanical relay is also in the circuit, I can still cut all power to the heater by simply turning off that master relay. Problem solved.

Practical Steps for Better SSR Safety Wiring

So, how do you actually wire this? It’s surprisingly simple. You’re essentially creating a “belt and suspenders” system where both have to be on for the device to get power.

- High-Voltage Path: The “hot” wire from your wall outlet goes to the input of your mechanical relay. The output of the mechanical relay then goes to the input of your SSR. Finally, the output of your SSR goes to your load (the heater, motor, etc.). The neutral wire can typically go straight to the load.

- Low-Voltage Control: Your controller (like an Arduino, Raspberry Pi, or PID controller) will need two output signals. One tells the mechanical relay to turn on at the start of the process. The second signal is the one that pulses on and off to control the SSR for temperature regulation.

When you want to shut the whole system down, your controller simply cuts power to the mechanical relay, and the circuit is safely broken, regardless of what state the SSR is in.

Don’t Forget the Supporting Cast: Fuses and Heat Sinks

This redundant setup is the core of the safety system, but two other things are absolutely non-negotiable for proper SSR safety.

- Always Use a Fuse: Your SSR should be paired with a properly rated fuse. The fuse is there to protect against over-current situations and is your first line of defense. A fuse is cheaper than a new SSR, and it’s definitely cheaper than a fire. For more on this, the folks at All About Circuits have a great guide on fuses.

- Use a Heat Sink: SSRs get hot, especially when switching heavy loads. Heat is their number one enemy and the most common cause of failure. An SSR running without a heat sink is an SSR that’s doomed to fail. Make sure you get a heat sink appropriately sized for the load you’re running. Most manufacturers, like Sensata (Crydom), provide detailed application notes on how to manage heat. Don’t guess—do the math or oversize it to be safe.

It might seem like a bit of extra work. But taking an extra thirty minutes to add a backup relay and a heat sink is a small price to pay for knowing your project won’t become a hazard. Build smart, build safe.